California’s Cannabis History

The Origins of California’s 100-Year War on Cannabis

by Dale Gieringer

California has a long history of leadership in cannabis legislation. Although cannabis prohibition is commonly dated from the first federal law, the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, cannabis or “Indian hemp” was originally outlawed in California in 1913, during the first, Progressive Era wave of anti-narcotics legislation.

The 1913 law received no public notice or press coverage. Rather, it was passed as an obscure technical amendment by the California State Board of Pharmacy, which was then leading one of the nation’s earliest and most aggressive anti-narcotics campaigns.

Under the board’s leadership, California became a nationally recognized pioneer in the war on drugs. Inspired by anti-Chinese sentiment, San Francisco had instituted the first known anti-narcotics law in the U.S. in 1875, an ordinance outlawing opium dens. By 1907, seven years before the US Congress restricted sale of narcotics by enacting the Harrison Act, the state Board of Pharmacy engineered an amendment to California’s poison laws so as to outlaw the sale of opium, morphine and cocaine except by a doctor’s prescription.

The Board followed up with an aggressive enforcement campaign, in which it pioneered many of the modern techniques of drug enforcement, including undercover agents and informants, criminalization of users, and anti-paraphernalia laws, climaxed by a series of well-publicized raids on pharmacists and Chinese opium dens.

During this time, cannabis was never an issue, its use as an intoxicant being rare in California. “Marihuana,” the Mexican name for the drug, was still unfamiliar as of 1913. Instead, it was commonly referred to as hasheesh or Indian hemp, an exotic vice of Asiatic foreigners and a handful of bohemians and spiritualists. Just a few scattered references to cannabis in California are known before 1913. Cannabis sativa was occasionally grown for hemp in the Central Valley. Imported cannabis indica was available for medical use in pharmacies. There is even one report of hasheesh cultivation by Middle Eastern immigrants near Stockton in 1895. Nonetheless, there existed no apparent public concern about its use at the time. In 1909, the police department of San Francisco reported, “there has been only one case of the use of Indian hemp or hasheesh treated in the Emergency Hospitals in six years, and that was accidental” (presumably an overdose).

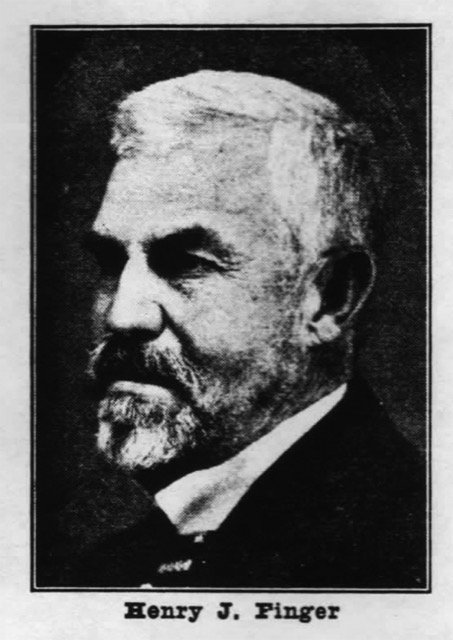

Nevertheless, Indian hemp had come to the attention of a prominent member of the California Board of Pharmacy, Henry J. Finger, author of the state’s poison control laws. A vociferous advocate of aggressive enforcement, Finger had been appointed along with Hamilton Wright, the chief architect of U.S. narcotics policy in Washington DC, to the U.S. delegation to the first International Opium Conference at the Hague in 1911.

Wright, a brash and enthusiastic drug prohibitionist (though like Finger an alcohol drinker), had been pushing to have cannabis included in federal drug legislation. “I would not be at all surprised if, when we get rid of the opium danger, the chloral peril and the other now known drug evils, we shall encounter new ones,” he wrote. “Hasheesh, of which we know very little in this country, will doubtless be adopted by many of the unfortunates if they can get it.”

Finger, a long-time proponent of aggressive enforcement in California, had similar ideas. In a remarkable letter to Wright, dated July 2, 1911, he urged that the Hague Conference take up the cannabis issue:

“Within the last year we in California have been getting a large influx of Hindoos and they have in turn started quite a demand for cannabis indica; they are a very undesirable lot and the habit is growing in California very fast...the fear is now that they are initiating our whites into this habit... We were not aware of the extent of this vice at the time our legislature was in session and did not have our laws amended to cover this matter, and now have no legislative session for two years (January, 1913). This matter has been brought to my attention a great number of time[s] in the last two months...it seems to be a real question that now confronts us: can we do anything in the Hague that might assist in curbing this matter?”

The “Hindoos,” actually East Indian immigrants of Sikh religion and Punjabi origin, had become a popular target of anti-immigrant sentiment after several boatloads arrived in San Francisco in 1910. Their arrival sparked an uproar of protest from Asian exclusionists, who pronounced them to be even more unfit for American civilization than the Chinese. Their influx was promptly stanched by immigration authorities, leaving little more than 2,000 in the state, mostly in agricultural areas of the Central Valley.

The “Hindoos” were widely denounced for outlandish customs, dirty clothes, strange food, suspect morals, and especially their propensity to work for low wages. Aside from Finger’s letter, however, there are no known reports about their using cannabis. To the contrary, their defenders portrayed them as hard-working and sober. “The taking of drugs as a habit scarcely exists among them,” testified one observer.

Nonetheless, Finger’s concerns were sympathetically received by Wright, who replied, “You certainly should have your legislature do something in regard to Indian hemp.” Delegates to the Hague Conference would reject Finger’s and Wright’s proposal to prohibit cannabis in the international treaty. However, the wheels for prohibition had been set in motion in California, where legislation to ban “narcotic preparations of hemp” was introduced in the 1913 legislature.

By this time, another menace had appeared on the horizon: “marihuana,” the Mexican name for cannabis leaf rolled into cigarettes - at that time a novel method of taking the drug - had begun to penetrate north of the border, carried by immigrants and soldiers during Mexico’s revolutionary disorders of 1910 - 1920. Though scarcely known to the American public, marihuana or “loco-weed” was noticed by the pharmacy journals, which surmised that it was a relative of Indian hemp or perhaps jimsonweed. In Mexico marihuana was typically associated with delinquents and soldiers, lending it a discreditable reputation for madness and violence. With this in mind, the Board duly added “loco-weed” to its 1913 legislation.

The 1913 Poison Act Amendments

The 1913 legislation passed with no opposition and no public mention in the press. Unlike previous narcotics bills, it was opposed by the state’s druggists, who voted against further changes in the poison laws in a poll of their membership. However, Finger and the Board were in good control of the legislature, which passed it unanimously.

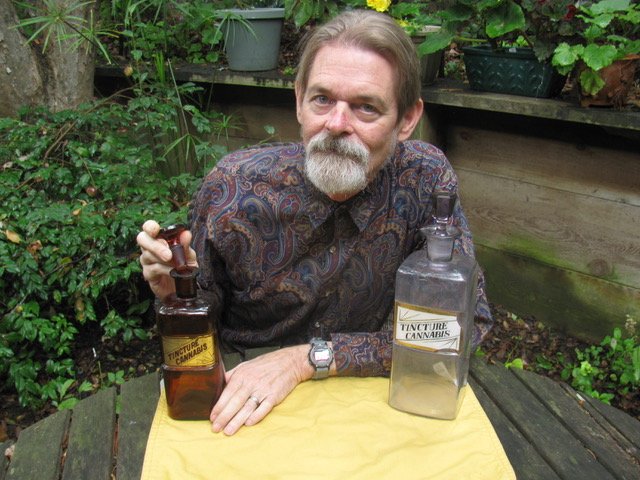

The new law, which took effect on August 10, 1913, amended the state’s poison law so as to ban the possession - but not sale - of “extracts, tinctures, or other narcotic preparations of hemp, or loco-weed, their preparations or compounds (except corn remedies containing not more than fifteen grains of the extract or fluid extract of hemp to the ounce, mixed with not less than five times its weight of salicylic acid combined with collodion).” The law was accidentally misworded so as to effectively ban the possession of medical hemp drugs as well as hashseesh and loco weed (except for corn remedies, which had negligible potency and were a popular, if medically dubious, product of proprietary drug manufacturers). In practice, the possession of hemp medications was never prosecuted, and they continued to be prescribed for years to come in California.

Of more concern to the Board was that drugstores sometimes sold marijuana to recreational users, as documented in an investigation of drugstores in southwestern states by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Bureau of Chemistry.

This loophole was patched up in 1915, when the legislature amended the Poison Act to outlaw sales of cannabis in the same way as opium and cocaine, prohibiting the sale of “flowering tops and leaves, extracts, tinctures and other narcotic preparations of hemp” except on prescription. Though the law permitted the possession of legally prescribed narcotics such as opium, the possession of hemp drugs (other than corn cures) remained independently, technically illegal under the 1913 paraphernalia provision, which remained on the books until 1937.

In later years, the 1915 law was erroneously remembered as the state’s first anti-cannabis law. This confusion, like the negligent miswording of the 1913 law, is evidence of the very obscurity of the cannabis issue. The fact is that cannabis was of no concern to anyone in California except the Board of Pharmacy. In the end, Finger’s cannabis-using Hindoos were merely a handy excuse for the Board to work its will. In the climate of the times, no more excuse was needed. The 1910s marked a high tide of prohibitionist sentiment in America. In 1914 and 1916, alcohol prohibition initiatives made the state ballot, and nationl prohibition was approved in 1919.

THE ADVENT OF MARIJUANA

Although passage of the 1913 law attracted no notice, the Board’s enforcement efforts soon brought marijuana to public attention. In 1914, the Board launched a publicized crackdown in the Mexican Sonoratown neighborhood of Los Angeles. In perhaps the nation’s first report of a marijuana cultivation bust, the Los Angeles Times reported that two “dream gardens” containing $500 worth of Indian hemp or “marahuana” had been eradicated (Sep. 10, 1914). According to police, the drug was surrounded by sinister legends of murder, suicide and disaster. After the initial crackdown, interest in marihuana subsided; not until the 1920s was its use reported in Northern California.

Other states enacted anti-cannabis laws in the 1910s: Massachusetts in 1911; Maine, Wyoming and Indiana in 1913; New York City in 1914; Utah and Vermont in 1915; Colorado and Nevada in 1917. As in California, these laws were passed not due to any widespread use or concern about cannabis, but as regulatory initiatives to discourage future use.

Ironically, it was only after marijuana had been outlawed that it began to become popular. Even while attitudes against drugs hardened during alcohol prohibition, marijuana became increasingly common in the 1920s. By 1925, it accounted for one-quarter of drug arrests in Los Angeles and 4% of those in San Francisco. By this time, penalties had been increased: possession and sale, which had initially been misdemeanors, became punishable by up to six years in prison. Despite this, usage spread inexorably. By 1930, marijuana accounted for nearly 60% of drug arrests in Los Angeles and 26% statewide, at a time when there were 878 total drug arrests in the state.

After taking a backseat to the Depression and World War II, usage resurged in the 1950s. Once again penalties were hiked, to a minimum 1-10 years for possession. Nonetheless, arrests continued to mount, reaching 5,155 in 1960. After that, usage exploded to epidemic proportions during the counterculture revolution, as pot-smoking hippies flocked to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district during the Summer of Love of 1967. In 1972, a hardy band of volunteers under the name of Amorphia placed the world’s first marijuana initiative on the ballot. Although the California Marijuana Initiative lost 2-1 at the polls, it did better than expected, laying the ground for the modern marijuana reform movement.

By 1974, California was staggering under a record 103,097 marijuana arrests, virtually all of them felonies. Overburdened by the costs of enforcement, the legislature decriminalized possession to a misdemeanor under the Moscone Act (sponsored by California NORML). Effective in 1976, the act made possession of one ounce punishable by a maximum $100 fine. Arrests promptly plummeted by 50% and felonies by 80%, saving the state an estimated $200 million per year. Nonetheless, state officials still struggled to suppress the illegal market, as cultivation and sales remained felony offenses, and California offered fertile grounds for a lucrative marijuana industry in its remote Emerald Triangle wilderness,

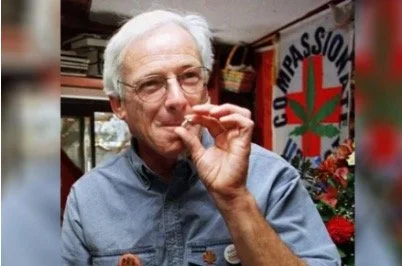

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients were discovering the medicinal value of cannabis for treating chronic pain, nausea and appetite loss from HIV and cancer, muscle spasticity, glaucoma and other conditions. In a campaign led by marijuana and gay activist Dennis Peron, San Francisco voters approved a citywide medical marijuana ordinance, Prop P, by the whopping margin of 80% in 1991. Activists went on to put a medical marijuana initiative, Prop. 215, on the state ballot, which was approved by 56% of the voters in 1996. Prop. 215 re-leglized both the possession and cultivation of marijuana for medical purposes with a doctor’s recommendation. For the first time since 1913, cannabis could be legally grown and used in California. Within a few years, hundreds of patients’ collectives were serving over a million medical users in the state. Thirty-eight states and fifty foreign countries have since followed California’s example with medical marijuana laws of their own.

Nonetheless, there remained a larger, non-medical market in California, accounting for over 77,000 arrests by 2008. Activists organized a new, adult use California legalization initiative, Prop 19, in 2010, which, though falling short at the ballot, gained enough votes to inspire subsequent, successful legalization initiatives in Colorado and Washington in 2012. Finally, in 2016, California voters followed suit by approving, Prop. 64, which legalized adult use under a system of state-licensed sales and production.

In retrospect, the legacy of California’s war on marijuana is one of dismal failure. The entirety of the modern marijuana problem occurred after the passage of the laws intended to prevent it. From the time that it was first banned in 1913 to 2016, the number of marijuana users in California skyrocketed from a handful to several millions. In the same time, there were over 2,670,000 marijuana arrests in California, including 1,300,000 felonies. Historically, it is significant that California, a pioneer in cannabis prohibition, was likewise at the forefront of the movement to decriminalize and legalize its use. It is also significant that this movement was led by votes of the people, against the almost universal opposition of government officials and law enforcement. For the primary champions of California’s 100 Year War on Cannabis weren’t the people, but rather government drug control agencies like the State Board of Pharmacy, which created it.

For more see: Dale Gieringer, “The Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California,” Flower Valley Press 2024; Original version: “The Forgotten Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California,” Contemporary Drug Problems vol. 26 #2 (1999).